Tribal Boarding Schools - help or threat? - languages & cultures

|

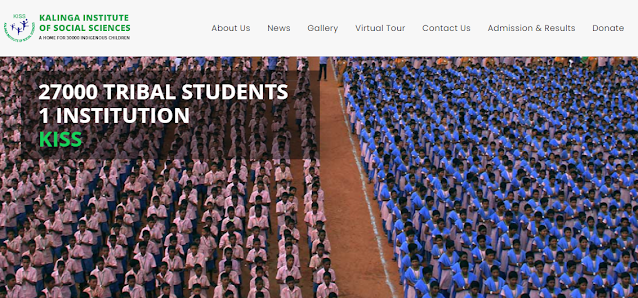

| KISS website screen capture |

A couple of weeks ago I was asking a few colleagues about the famous Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS) Boarding school in Orissa. A sponsored Internet article stated that they were involved in mother-tongue-based multilingual education. But this week I came across research which is questioning previously published reports about the tribal boarding schools and KISS in particular.

KISS Is quite an impressive institution. There are 27,000 pupils from kindergarten to postgraduate enrolled. The KISS’ website states that the school and its associated university are the world’s largest “anthropological laboratory.”

In The Travesties of India’s Tribal Boarding Schools two researchers from the University of Oxford are challenging the basic foundation on which the school is functioning. They conducted over 50 in-depth interviews with KISS ex-staff, ex-students and their parents. They claim they found similarities to what happened in North America in the previous century in the residential schools which were set up to “civilise” the children from indigenous communities. They also looked at other tribal boarding schools and found similar conclusions.

The critical conclusions of their research are quite in contrast with research done by Christine Finnman, a cultural anthropologist and professor at the College of Charleston in South Carolina in 2016. She spent six months at the school and interviewed 160 students and wrote Indigenous Education and Hope in India. She concluded that the school upholds the dignity of the children and their cultures: “The school is unlike the boarding schools for Indigenous children that are part of the painful legacies of North America and Australia.”

The Oxford researchers claim that children at the boarding schools are more or less forced to give up and disconnect from their roots: "Children at the Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences dress in blue and pink uniforms, their hair is cut short, and no traditional ornaments are allowed—just as tribal knowledge and value systems find little place in what is taught. Children reportedly stay without a break for 10 months a year and, we were told, have limited contact with their families.” With regard to multilingual education they write: "KISS does have a Mother-Tongue-Based Multilingual Education program. However, its lab appeared to be operating at minimal levels when we visited, and several experts have informed us that it exists largely for show.” If that is the case, it would be quite a sad state of affairs which would be good to hear others speak to.

Finnman’s interpretation of what she observed is quite different: “Unlike now-shuttered Indigenous boarding schools in the West, students are not forced to attend KISS, and they are not stripped of their tribal cultures and languages; rather, parents eagerly seek out space for their children at KISS, and the school exhorts students to be proud of their heritage and to keep their languages and cultures alive.”

It seems this discussion shows the need for more research on the long-term impact of present education practices for tribal students. The Oxford researchers end the article with the following advice: "Culturally sensitive initiatives in tribal education from many parts of India can be rejuvenated, and contemporary alternatives can be provided with more extensive support.” Let's keep on learning!

Regards,

Karsten